Promises Written On The Ice, Left In The Sun

Promises Written On The Ice, Left In The Sun

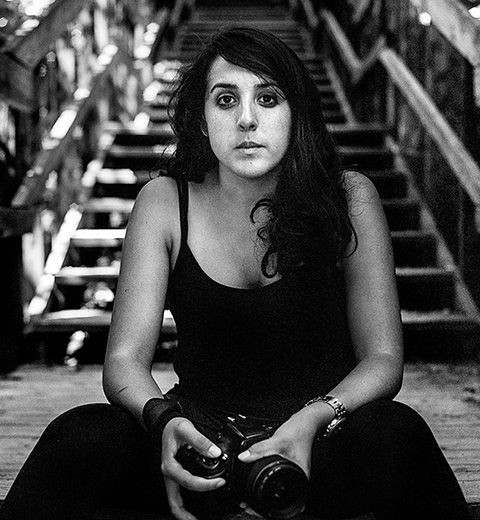

Kiana Hayeri

October 24, 2022

Hafiza (70) reveals an open wound on her throat; a wound that doctors believe is caused by grief. Badakhshan, April 8, 2021. Four of Hafiza’s sons opted for different paths: they joined the army, the Taliban, or an anti-Taliban militia.

LFI: What has changed for you, personally, since last summer?

Kiana Hayeri: The biggest change has been in my personal life – losing friends from my social circle and daily life. The rhythm of our work has changed, as well. We don’t do as much breaking news as before. The war and violence has come to an end; however, dealing with the Islamic Emirate takes up our time and energy; and most people are also terrified to speak up. A blanket of oppression is suffocating everyone.

What hopes do you have for Afghanistan? Or how pessimistic are you about the future?

I wish I could be more optimistic about the future of Afghanistan; but, with every new ruling the Islamic Emirates make, part of that hope vanishes. It’s very difficult for most of us to envision anything positive coming out of this change of power.

The photographs were taken between 2018 and 2021. Have any of the images been published before?

Yes, of course. These are photos shot on different assignments for different publications. But they have never appeared together as one coherent body of work.

Which images from the LOBA series are particularly important to you?

I think that, when narrowing down a huge body of work produced over 4 years to 20 images, almost every frame is special. But for me, the photo of Hafiza, particularly, feels special and symbolic. I feel that Hafiza, a 70-year-old mother whose four sons became enemies of each other, and whose open wound is believed to be caused by grief, stands for what Afghanistan has gone through in the last 40 years; and where it is today. It’s a country with open wounds that is struggling to heal.

Have you already thought about what you will do with the prize money?

I'm in the midst of designing and publishing a photo book, which is specifically about the work I created inside Herat Prison, and with which I also won the Robert Capa Gold Medal last year: it’s a body of work that's very close to my heart, and it took on a different meaning after the Taliban took over the country and, in my opinion, put women into a larger prison called Afghanistan.

All the images of the LOBA series and further information can be found on the LOBA webpage.

The LOBA catalogue 2022 also contains all the images and an interview with the photographer. The winners and all shortlisted candidates of LOBA 2022 will be presented in issue 8/2022 of the LFI magazine.

Kiana Hayeri+-

...was born in 1988, in Tehran, Iran, where she grew up, before emigrating to Toronto, Canada, as a teenager. In 2021, she received the Robert Capa Gold Medal for her Where Prison Is a Kind of Freedom series, documenting the lives of Afghan women in Herat Prison. In 2020, she received the Tim Hetherington Visionary Award; and became the sixth recipient of the James Foley Award for Conflict Reporting. Hayeri is a Senior TED Fellow and works regularly for The New York Times and National Geographic. She lives in Kabul, Afghanistan. More

Hafiza (70) reveals an open wound on her throat; a wound that doctors believe is caused by grief. Badakhshan, April 8, 2021. Four of Hafiza’s sons opted for different paths: they joined the army, the Taliban, or an anti-Taliban militia.

Shortly before the recording of the show Afghan Star, Hasib Sayed – Aryana Sayeed’s husband and manager – did a little photo shoot for social media, after her hair and makeup were done in their safe house.

Nafas (20), who killed her husband, socialises with their cellmates and other incarcerated women. Herat, April 1, 2019. At the age of twelve, she had been made the second wife of an addicted and abusive man.

A group of high school students walk a two-hour journey, everyday, through Fouladi Valley, to go to the closest school to their village. Bamian, September 3, 2019. The Taliban have now closed all secondary schools for girls, indefinitely.

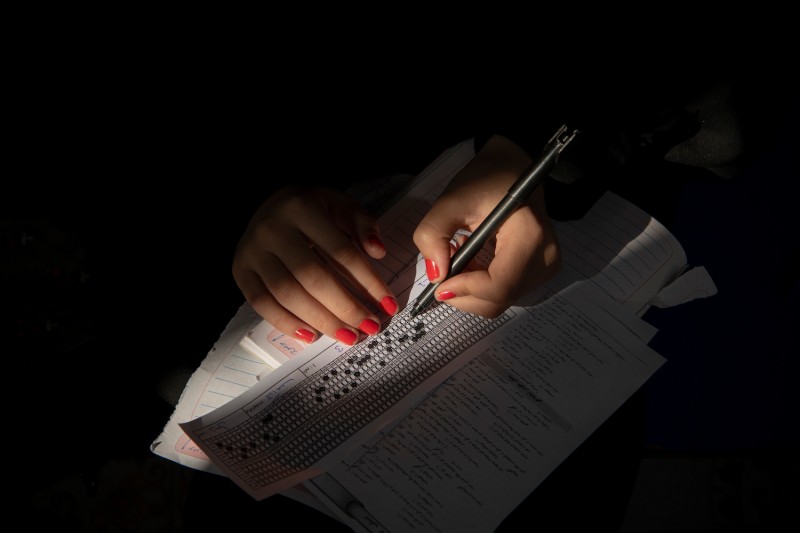

A group of girls take their weekly test at the Daqiq Institute, on a Friday morning, in preparation for university entrance exam. Balkh, October 8, 2021. The Taliban have now closed all secondary schools for girls, indefinitely.

Afghan girls patrol, during an ambush scenario, at Marshal Fahim Qasim Military Academy, north-west of Kabul. February 20, 2019. Since the Taliban took over Afghanistan, most women officers and soldiers were removed from service. Many have now gone underground.

In a local school that was set up by a teacher in the village of Hussain Khel, 25 high school girls cram together, everyday, to make the most out of the few hours of schooling.

Fakhria, her daughter Foroohar, and her friend Masooma wear masks for fun, and dance at the wedding anniversary of a friend. Kabul, February 18, 2021. After the Taliban took over Afghanistan, Fakhria, who often criticises the Taliban and stands up for women, had to flee the country.

Zohra (27), a survivor of an acid attack by her husband and her mother-in-law, sits in a room while nurses change the dressing on her face. She has lost an eye, but is otherwise expected to recover.

In the basement of an unfinished mosque, women mourn daughters and sisters killed in an attack. May 9, 2021. The powerful explosions, in the morning in front of a high school, killed at least 90 people, and injured a further 150. Many were teenage girls who were just coming out of class.