The Significant Moment of Yevgeny Khaldei

The Significant Moment of Yevgeny Khaldei

Ernst Volland

May 23, 2017

An earlier version of the famous image, still depicting the supporting soldier with a watch on each wrist. The victory flag atop Berlin’s Reichstag, 2 May 1945

You met Yevgeny Khaldei for the first time in Moscow in 1991. How did the meeting come about?

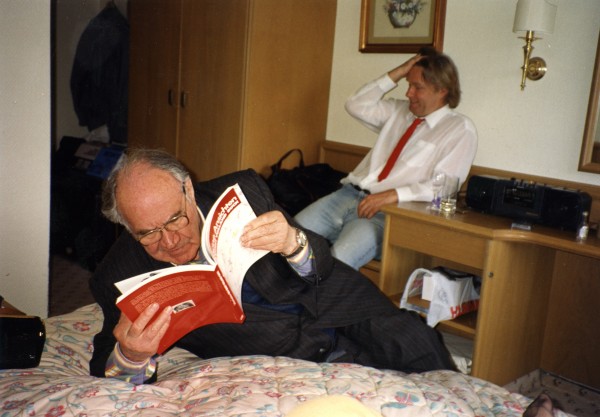

Walter Momper, the former ruling mayor of Berlin, invited me to join a ten-person, SPD delegation going to Moscow to lay down a wreath at the Kremlin wall on 22 June, 1991, in memory of the attack by the Germans (Operation Barbarossa) that ended up costing the lives of 20 million Russians. Cultural encounters were part of the trip, among other things with five war photographers.

One of them was Yevgeny Khaldei, whose name and work were unknown to me. When he showed me some of his photos, the flag atop the Reichstag in 1945, photos of the Potsdam Conference and the Nürnberg Trials, I was more than surprised. I started talking with Khaldei. He invited me to his apartment on the outskirts of Moscow, but we were leaving the same day. A year later I returned to Moscow on my own steam and visited Khaldei. That was how our collaboration began.

How did this collaboration turn into a friendship?

When you have a father who was one of the soldiers involved in the attack on the Soviet Union, and who also fought in Ukraine, Khaldei’s homeland, it is especially lucky that a friendship was even able to develop. When questioned at openings of exhibitions in Germany, he would say, “I can forgive, but I can not forget. My father and two sisters were thrown alive into a coal pit, with 70,000 others. That was the Germans.” I am sure, however, that after the war Khaldei and my father would have got on. They were similar types.

How would you characterise Khaldei? What was your experience of him?

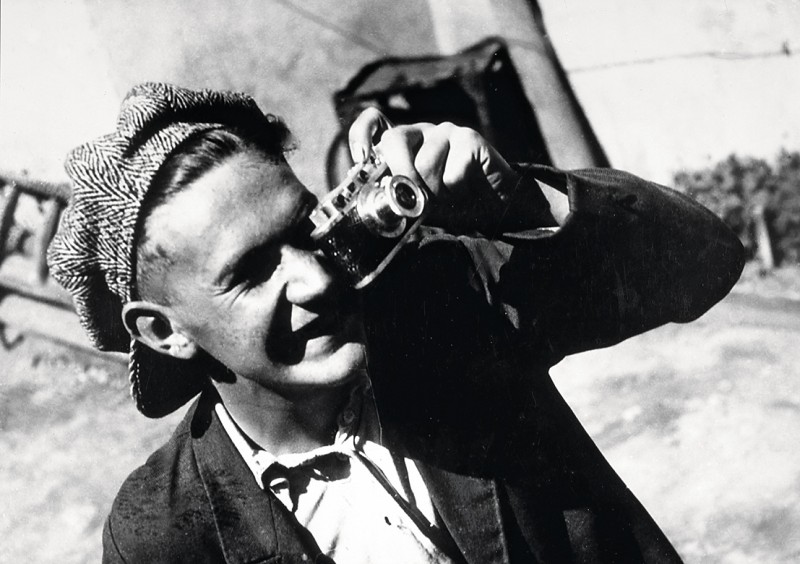

Generous, nearly blind, walking with a stick, with a talent for languages, humorous, direct, a hard drinker. In love with photography and with the technology. Proud of his Leica. He always had to have it with him. Blessed with an enormous memory. Looking at a photo, he could remember every place, every person in the picture.

How do you see your own role? As an administrator of his legacy, a curator, a friend?

It has all come together. On the whole, working together was not easy, because after a certain time of knowing him, his lewdness suddenly appeared everywhere, sometimes with dishonest intentions. Difficult also because the relationship between Russia and German was complicated, and was and is loaded with resentment, which had a negative impact especially with regard to sponsoring the exhibitions and books. We are intending to sell our unique Khaldei collection to a museum.

How many of his works do you own?

Heinz Krimmer of the Voller Ernst agency and I own around 500 original photos, printed by Khaldei. Most of them are signed and dated. Khaldei trusted me right from the beginning, and I was able to deliver results, such as the first solo exhibition in the West in 1994, or the first book,!Von! Moskau nach Berlin, the same year.

Is there any one picture from his body of work that’s special for you?

The amazing thing about Khaldei’s work is his consistent photographic quality. He was able, also thanks to his flexible Leica, to find the appropriate visual composition in significant historic moments. There is good reason why he is known as the Russian Frank Capa.

The Soviet flag atop the Reichstag, Berlin 1945, is his best known motif, and it was always my wish that this photograph, as well as his entire oeuvre, would be associated to the name Yevgeny Khaldei. I think that his Reichtag photo is his most important one, because it symbolises the end of Fascism, the end of the Second World War, and the end of Hitler. Khaldei’s photographs say: never again war.

Interview: Ulrich Rüter

All photos: © Sammlung Ernst Volland/Heinz Krimmer/Jewgeni Chaldej

The film Jewgenij Chaldej – Fotograf der Weltgeschichte (Bernd Siegler, Medienwerkstatt Franken, 2003), which can be seen on Vimeo, offers an insightful look into the photographer’s life.

Ernst Volland+-

Born in 1946, Ernst Volland studied Fine Arts in Hamburg and Berlin. His caricatures, posters, photo montages and sketches have been widely exhibited and published in numerous catalogues. In 1987 he founded the Voller Ernst Photo Agency in Berlin with Heinz Krimmer.

Volland has published Yevgeny Khaldei’s work around the world in exhibitions and books, including, Kriegstagebuch (Verlag Das neue Berlin, Berlin 2011); Der bedeutende Augenblick (Neuer Europa Verlag, Leipzig 2008, complementing the exhibition at the Martin Gropius Building in Berlin); Heinz Krimmer, Ernst Volland: Von Moskau nach Berlin. Bilder des russischen Fotografen Jewgeni Chaldej (Parthas Verlag, Berlin 2002). More

An earlier version of the famous image, still depicting the supporting soldier with a watch on each wrist. The victory flag atop Berlin’s Reichstag, 2 May 1945

The poet Yevgeniy Aronovich Dolmatovsky (1915–1994) was a Red Army lieutenant at the liberation of Berlin. After the German troops surrendered on 2 May 1945, he recited poems at the Brandenburg Gate. This picture, taken on the same day, made him widely known

Khaldei in 1937 with his first Russian Leica, the FED – named after Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky (1877–1926), founder of the secret police agency Cheka. The camera was manufactured in the Dzerzhinsky Commune for homeless youths in Kharkiv (Ukraine). After acquiring the licence, the commune produced Leica copies from 1932 on

Berlin after the end of the war. A Red Army member directs the traffic in front of the Victory Column