Peru – A Toxic State

Peru – A Toxic State

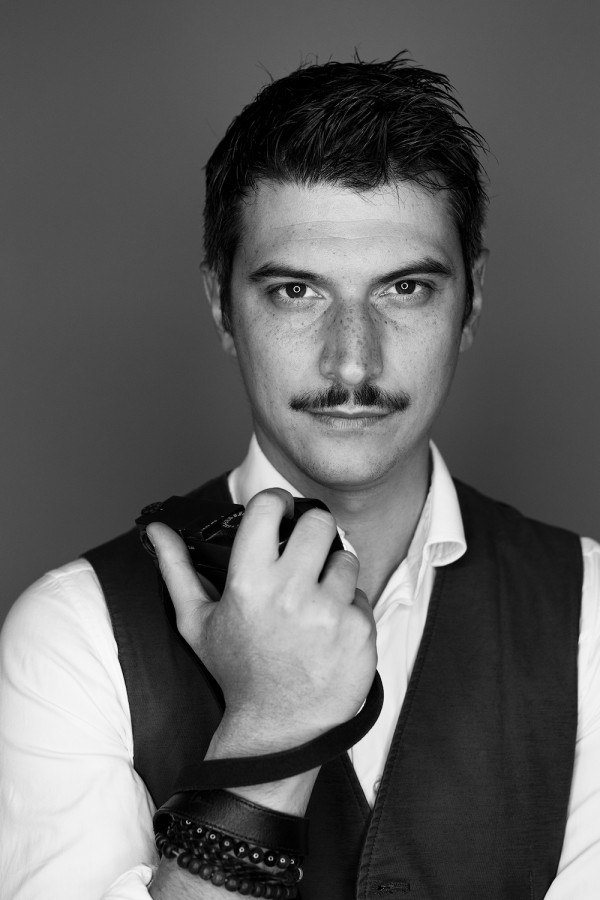

Alessandro Cinque

April 15, 2021

LFI: What are the biggest influences on your photographic work?

I have always been attracted to classic photography; like, for example, the Magnum photography of the 80s and 90s. I have always been fascinated by everything that can be defined as "classic". I like to listen to classical music and I'm convinced that even in one hundred years, with the arrival of future musical trends, people will continue to listen to operas. I think the same thing about photography. In recent times, I've been approaching South American indigenous photographers. I believe that South America is currently experiencing a generational revolution and is finally creating a visual language of its own, which is why I like to compare the work of young local photographers with the work of the great Latin American photographers – first and foremost, Martin Chambi.

Peru - A Toxic State has been an ongoing project since 2017. Could you describe its importance to you, personally?

This project changed my life. As time went on, I became more and more involved with these people's stories and made decisions that turned my life upside down. Before this project I was working on small stories, but I felt that it wasn't enough. I felt superficial; I wanted to understand and witness deeper.

I was travelling in Peru between 2017 and 2019, while being based in Italy, and I was starting to realize that I was still photographing and telling the same stories. I was feeling stuck. My photography had to change; and to do that I had to change.

I believe there is an unwritten agreement between subjects and photographer. The subjects always provide what they have, their image and their story. The photographer must feel the importance of this responsibility and trust and make sure that these people's stories are heard and seen by as many people as possible. Moved by this moral responsibility, I decided it was time to do more, and in December 2019 I moved to Peru to understand Peruvian society and culture by living it every day. I aimed to start changing myself and consequently to change my photography. I left my comfort zone; but right now this is my priority.

Your project is still ongoing. Will it ever come to an end? What do you make the end of the project dependent on?

I want the project to be useful for local people. I want to inform about their situation. To date, I've worked in six mining towns and would like to photograph five more. This project should be understood as a journey through time and space.

I'm working on finding grants and funding to continue with new cities and to finish photographing. In the last few months I've been working on a fanzine, which serves as a visual and temporal map of the cities I've already photographed. It will be accompanied with texts in both Quechua and Spanish. Once it is ready, I want to gift this fanzine to community leaders to inform them in detail about what is happening near them.

Beyond publications, awards and grants, which serve to fund the work, I hope this work is useful to the people I photograph. To date, my greatest satisfaction is that this work has been chosen by a professor at a Canadian university, to include it in the study program, and that, through an NGO, it has reached the United Nations as a visual map. At the end of it all, I would like this project to become a book.

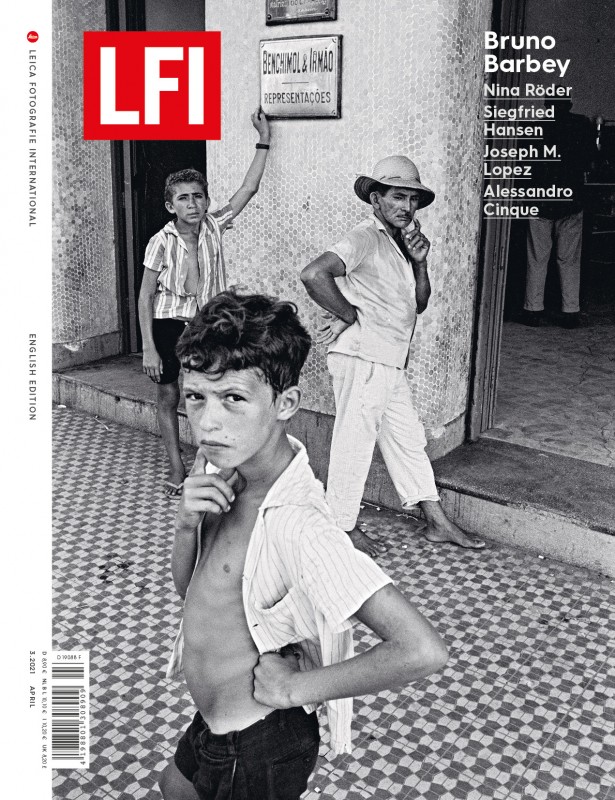

LFI 3.2021+-

Find out more about his project in the new LFI 3/2021. More

Alessandro Cinque+-

Social and ecological issues are at the forefront of Cinque’s work. In 2017, he documented gold mining in Senegal, and merchandise smuggling on the border between Iraq and Iran. In 2019, while studying at the International Center of Photography in New York City, he portrayed the Italian-American community in Williamsburg and photographed abandoned uranium mines in the Navajo Territories of Arizona. More