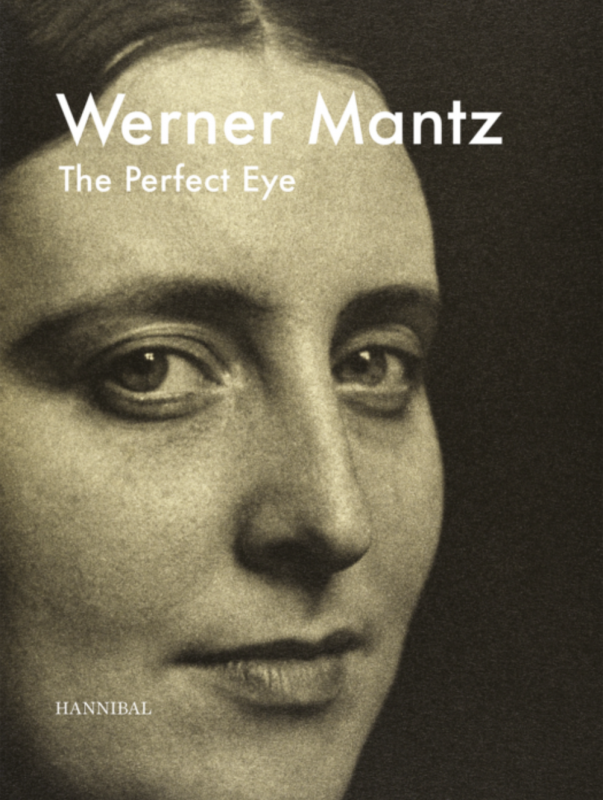

Book tip: The Perfect Eye

Book tip: The Perfect Eye

Werner Mantz

February 13, 2023

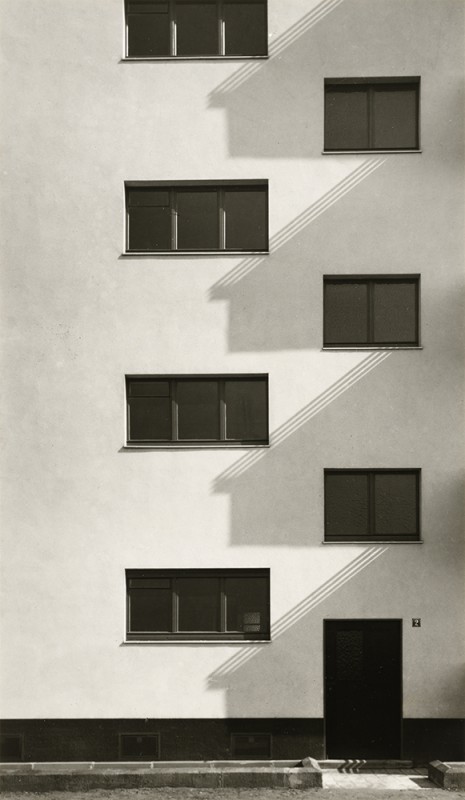

Housing estate, Cologne Riehl, 1929 © Werner Mantz/Museum Ludwig

In the 1920s, along with August Sander, Hugo Schmölz and his son Karl Hugo Schmölz, Mantz was considered one of Cologne's most influential photographers. Even so, there has never been a comprehensive retrospective of his work in Germany. Fortunately, however, the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht is currently hosting a magnificent exhibition of his work, accompanied by a thick catalogue published by Hannibal Verlag. The fact that Mantz's work is being exhibited in this Dutch city some forty years after his death can be explained by his biography. In addition to his photography atelier in Cologne's Hohenstaufenring, he had already set up a second studio in Maastricht in 1932. It was not only the tough economic situation in Germany that had led to this step, but, more importantly, the rising National Socialism that threatened his very existence due to his Jewish heritage. He left Cologne in 1938, following the November pogroms, and moved permanently to Maastricht. The commissions he received there changed his subject matter: now his focus was more on photographing people, especially children, and everyday subjects. His static architectural photography expanded to include more spontaneous portrait and snapshot photography.

Even so, it is his architectural photography that is the focal point of both the book and the exhibition; though some of his personal work, especially his portraiture, is also present. The “perfect eye” is what it is all about: a successful tribute to Werner Mantz's work and life, including supplementary texts in the book, and an overall generous supply of his photography.

Werner Mantz: The Perfect Eye+-

With texts by Frits Gierstberg, Stijn Huijts, Huub Smeets, Charlotte Mantz and Clément Mantz.

320 pages, over 270 black and white images, 32 x 24 cm.

Editions available in English, Dutch, and German.

Hannibal Books

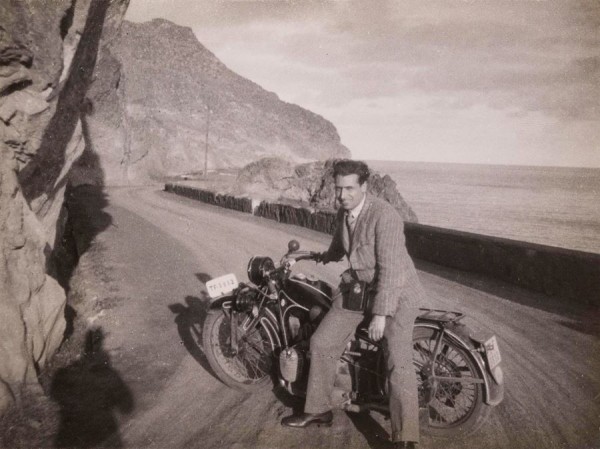

Werner Mantz+-

...was born in Cologne on April 28, 1901. He took his first photographs with an Ernemann camera when he was 14. He studied at the Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt für Photographie, Chemie, Lichtdruck und Gravüre (Institute for Teaching and Experimental Photography, Chemistry, Collotype Printing, and Engraving) in Munich from 1920 to 1921. He had his first studio in his parents' flat in Cologne in 1921, and in 1932 set up a second photo studio in Maastricht, Netherlands, in collaboration with Karl Mergenbaum. In 1939 he married his wife Grete with whom he had five children. The Cologne studio was closed. In 1940 he was drafted into the German Armed Forces for three weeks, before being discharged again due to his Jewish ancestry. After moving to Eijsden (NL) in 1968, he finally closed his Maastricht studio in 1971. In the 1970s he was rediscovered as a German modernist architectural photographer. Mantz died in Maastricht on May 12, 1983. More

Housing estate, Cologne Riehl, 1929 © Werner Mantz/Museum Ludwig

Café Wien am Ring, Cologne 1929 © Werner Mantz/Nederlands Fotomuseum

Child-care, Housing Estate Neu-Rath, Cologne-Mülheim 1930 © Werner Mantz/Museum Ludwig

Water tower, Ford plant, Cologne-Merkenich 1930 © Werner Mantz/Museum Ludwig

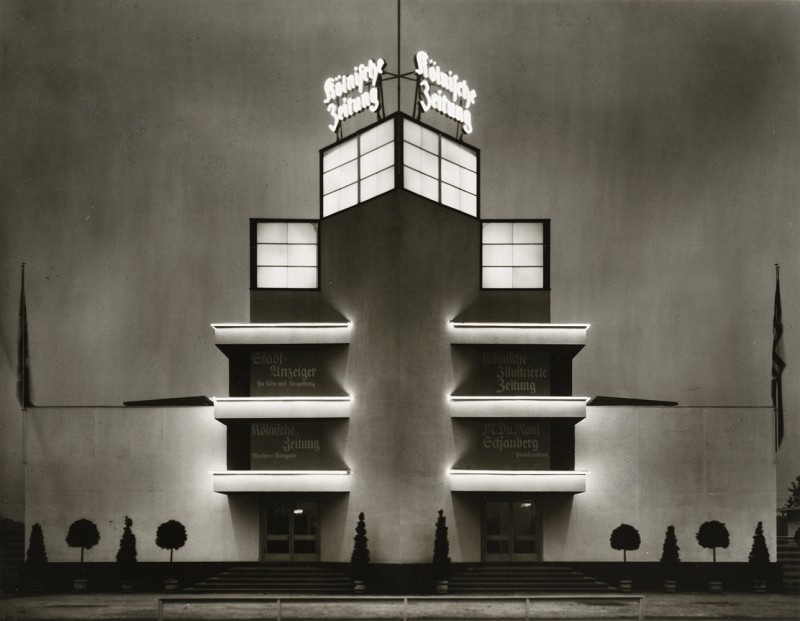

Kölnische Zeitung building at Pressa, Cologne 1928 © Bonnefanten Collection

Housing estate Cologne-Kalderfeld, house entrance, 1930 © Bonnefanten Collection

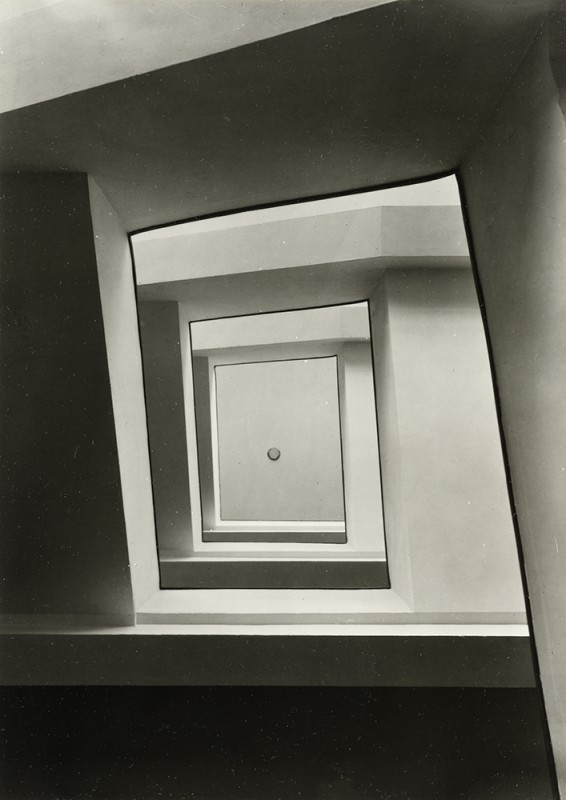

Stairwell, Ursulinen Lyceum, Cologne 1928 © Bonnefanten Collection

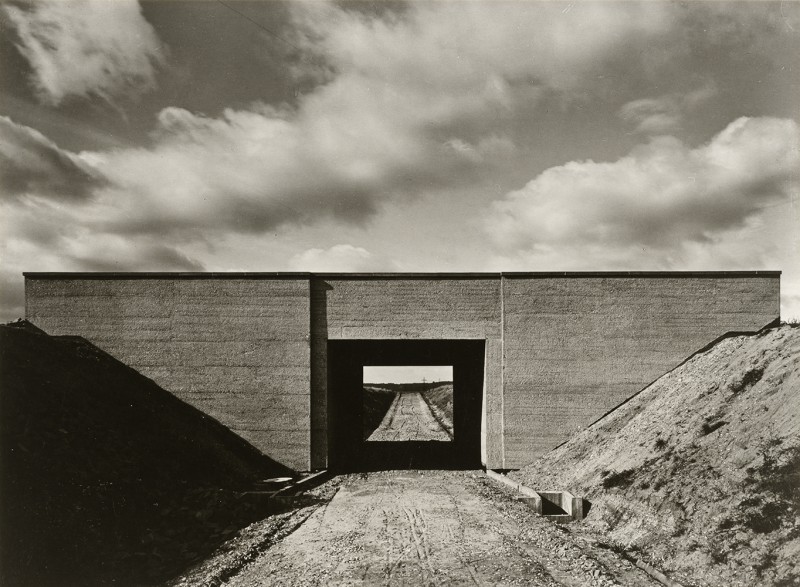

Bridge, Cologne 1927 © Bonnefanten Collection

Housing estate Kalkerfeld, Cologne 1928 © Bonnefanten Collection