World Ethno Games

World Ethno Games

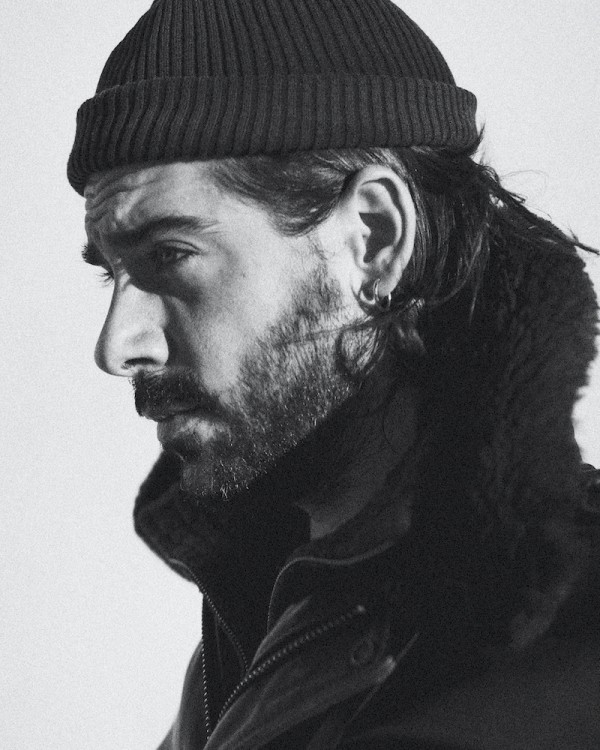

Maxime Fossat

February 3, 2022

A member of the festival security service walks past the main hippodrome of the event, while Kyrgyz dancers are rehearsing in the background

Maxime Fossat: Maksat Sydykov, a good friend of mine and former international ballet dancer, was hired as a choreographer for some of the shows that were to be held there. He wanted me to be part of the trip, so that I could come up with photographs that would look different to the usual corporate photography the organizers were aiming to produce. Backed by my portfolio, he proposed me to the board of the Ethno Games Confederation (emanation of the World Nomad Games held in Kyrgyzstan in 2018).

How did these games come to Saudi Arabia?

Saudi Arabia wanted to buy the rights of the upcoming Ethno Games, in order to create the world biggest Ethnic Festival on their soil. The first edition, held alongside the King Abdulaziz annual Camel Festival, was to be a test before signing up for 10 years. The communications team was interested in taking me with them, and offered that I join the delegation for the whole duration of the event (almost a month). That is how I ended up being the only French person among a crowd of 1200 Kyrgyz.

Your focus seems to be on the Kyrgyz participants. Why was that? You are based in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. What is your connection to the country?

I've been based in Bishkek for several years now, and I work here with press and institutional photography. I have developed a rather large network in the country, which allowed me access to this event. The Ethno Games Confederation is a Kyrgyz private structure, backed by the Ministry of Culture. As the Saudis wanted to buy the rights to the event for 10 years for a substantial sum of money, Kyrgyzstan put a maximum amount of effort in organizing and displaying the festival, in the hope that Saudi Arabia would eventually buy it. This explains why 1200 of us, plus all the animals, came from Bishkek on charters flights, and why I was mainly focusing on the Kyrgyz.

What is your focus when taking pictures?

That is quite a difficult question to answer. I work mainly (if not exclusively) with a 35mm, so, first of all, I would say that I tend to focus on the framing and distance to my subject. These are what matter the most to me, alongside a well balanced composition, in order to come up with a consistent body of work. On the other hand, I am not too picky when it comes to light. I only tend to avoid scenarios with too much contrast in daylight situations. I’m probably a bit stubborn about this point, but I genuinely dislike burned whites and, as soon as I encounter a scene where I know that some parts of my photographs will come up burned when correctly exposing my subject, I give up on shooting it. In the case of this specific work, I went there with no expectations, and not really knowing what I wanted to come back with. I quickly realized how surrealistic and, in a way, kitschy this whole environment was; so I started looking for scenarios that could reflect that aspect.

What were the biggest challenges you faced there?

The event was held 250 km north-east of Riyadh, in the Ad-Dhana desert. We were staying in camps right next to the festival site. As a result, I would say that the biggest challenge was the isolation: the closest town was 30 km away, we had no means of locomotion, and were asked to remain on site. That kind of gave many of us the feeling of being held in custody by the Saudis, unable to discover anything other than what was given to us to see at the festival site. So yes, even though it didn’t come from the Saudi side, but rather from the organizers' side, our freedom was quite limited.

And what challenges were there on the technical side?

The dust and sand were quite challenging. Out of the 25 days there, I can recall at least 6 days of sandstorms. The dust raised by the winds is so thin that it literally infiltrates everything. I got quite excited the first day of a sandstorm, which happened at a really early stage of our stay. The light was crazy, clouds of sands and dust covered and blurred all the surroundings, the kind of atmosphere any photographer would dream of; but after a couple of hours shooting outside, the dust had got inside my M10 viewfinder – and probably more areas of the camera and lenses that I couldn’t see –, so to be on the safe side and avoid any problems, I decided to get back inside. I then realized that, unfortunately, this was the biggest challenge: I wouldn’t be able to photograph on windy days.

How did you prepare yourself?

I had my usual set up: a Leica M10 together with my Summilux 35mm f/1.4 ASPH, a Summicron 28mm f/2 ASPH and a Summicron 50mm f/2, along with a set of cleaning tools (that I have never used as much as during that month). As it was March, heat wasn’t an issue. The hottest it got was probably around 28 degrees Celsius, and in contrast the nights were pretty cold, sometimes around 3 or 4 degrees Celsius.

What did you like about the camera and the lenses?

For me, compactness and discretion are the key features of a Leica. Adding the optical quality and fast lenses, makes it a great tool for this kind of work.

Maxime Fossat+-

Born in Bordeaux, France, in 1988, the documentary photographer is currently based in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. His first background was in wood work. In 2007 he started studies of Photography and graduated from the ETPA Photographic School in Toulouse (France), in 2009. He then worked as a fundraiser for various international NGOs in Switzerland. In 2015 he became a professional photographer. Since then, his work has been published in The New York Times, Le Monde, Zeit Magazin, Libération, The National, United Nations, Doctors Without Borders, USAID, among others. More

A member of the festival security service walks past the main hippodrome of the event, while Kyrgyz dancers are rehearsing in the background

Kyrgyz horse riders during a night-time rehearsal of the main show, that was to be performed in front of Prince Mohamed Bin Salman later during the course of the festival

Kyrgyz and Mongol dancers pose for a portrait in their traditional outfits

Kamelbesitzer beobachten aufmerksam eine Jury, die ihre Kamelherden bewertet. Der Preis für das schönste Kamel beträgt 32 Millionen US-Dollar.

Bedouins immobilize a camel that is about to be tested with echography tools in order to make sure it hasn’t been botoxed. Previous editions of the King Abdulaziz Camel Festival saw 12 camel owners being disqualified for use of botox in their camel lips

Bedouins getting their camels ready for a race

Camels reaching the final line of a race

Saudis looking at a show performed within the framework of the Ethno Games Festival

A member of a Kyrgyz dancing group smokes a cigarette in between rehearsals

A sandstorm hits the festival

Saudis and Kyrgyz are locked in a closed, outdoor area, watched by the Royal Guard while waiting for Prince Mohamed Bin Salman to leave the festival site after the closure ceremony

A tribune under construction prior to the launch of the festival