Books: Éditions lamaindonne

Books: Éditions lamaindonne

David Fourré

December 13, 2019

What inspired you to become a publisher of photo books?

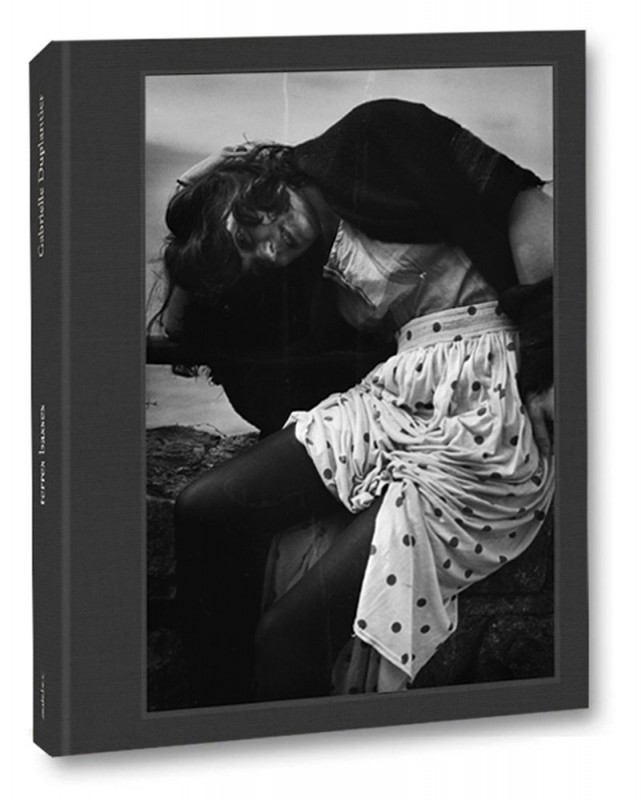

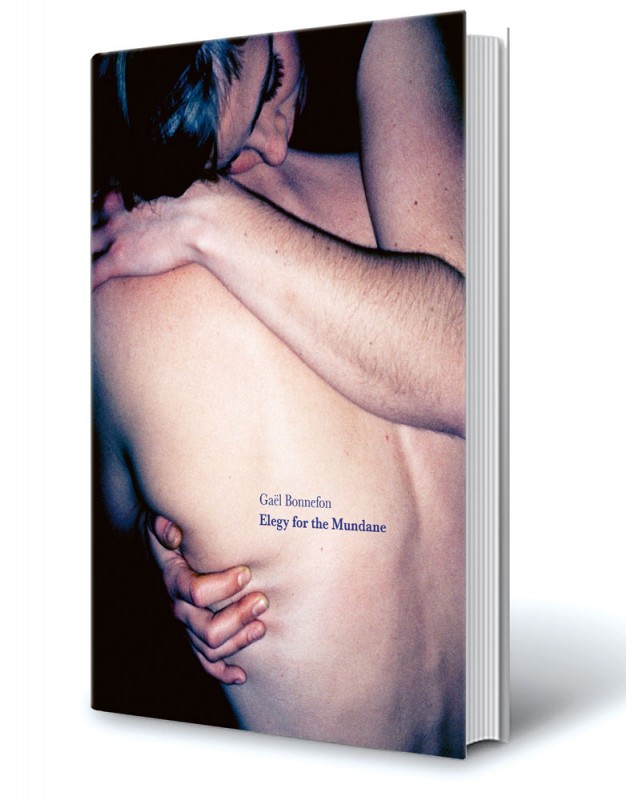

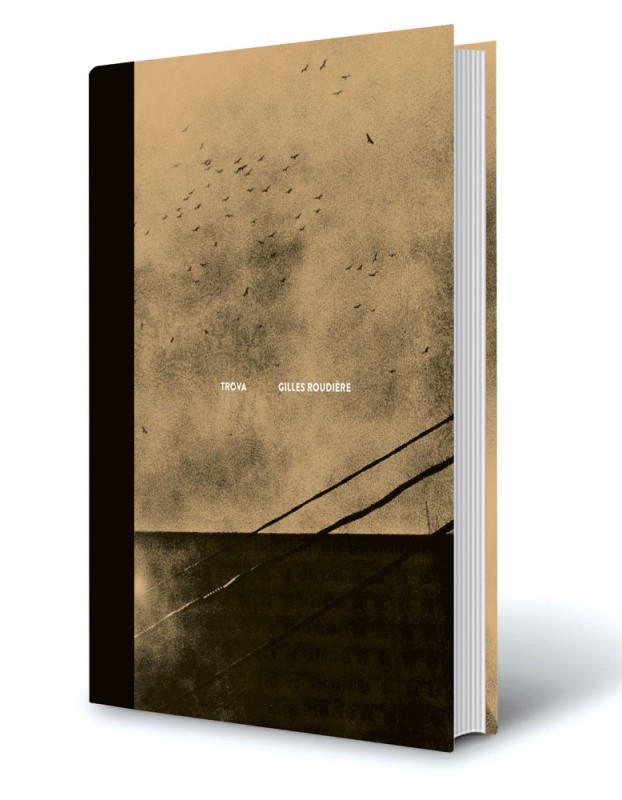

David Fourré: I’ve been working in the publishing industry for more than 20 years. The first photo book I ever published was a friend of mine’s project on Mali in 2010. After that, I realised that I wanted to continue on this journey. Before long, I had to come up with a name for the publishing company – and this is how lamaindonne was born. Shortly afterwards I met Julien Coquentin, and we published a book about Montreal which was very well received. The enthusiastic press coverage increased our public visibility. I went on to meet other talented young photographers – starting with Gabrielle Duplantier, followed by Ljubisa Danilovic and, more recently, Gilles Roudière and Gaël Bonnefon. Our next projects are already underway.

In 2019 you released three books of photographs by Gilles Roudière, Gaël Bonnefon and Gabrielle Duplantier, who seem to share a relatively similar visual approach. Was this a coincidence?

I’m not sure just how similar their styles really are. It is true that all three of them seek to create intimate, vibrant images that might be described as expressionistic. And they are all members of the Temps Zéro photographers’ collective, along with artists such as Alisa Resnik, Michael Ackerman and Martin Bogren. I very much connect with their work and the way in which they each convey the intimacy, suffering and joy of the human soul. However, they each have their own language, their own universe and unique personality. As for my editorial approach, I wouldn’t say that I follow a specific strategy. However, looking back over the photo books I have published to date, I can see that they all culminate in a similar position: a place where photography is an everyday practice that seamlessly blends into ordinary life, so that the human aspect is always palpable.

With that being said, how do you select the photographers whose work you publish?

I’m currently releasing no more than two to three volumes a year. With such a moderate pace, it’s not difficult to devise a programme spanning the next two to three years. At this point, the number of annual publications is limited due to financial restrictions, which means that I do sometimes miss out on great projects because I can’t afford to publish them. As for choosing my photographers: on the one hand, there are those who I have already worked with; if Gabrielle Duplantier offers me another series, I will certainly want to publish it. Of course, it is equally important to foster relationships with new photographers; this year, for example, I am working with Gilles Roudière and Gaël Bonnefon. In any case, I am not following any preconceived or clearly defined guidelines. More than anything, my decisions are based on instinct and the interactions I have with the photographers.

Another trait these three books have in common is that they are almost entirely devoid of text. What was the thinking behind this?

I’ve really been pondering the role of written text in photo books. This is not governed by any specific rules. In Terres basses, we deliberately decided to offer the reader no clues relating to the context of the images. We wanted the photographs, and the sequence in which they were presented, to speak for themselves. For Le Désert russe by Ljubisa Danilovic, we reproduced the email he had sent to me to introduce his work. It’s a fantastic text, very illuminating and certainly a highly relevant accompaniment to the images. In my opinion, if the photographer is able to put their own thoughts into writing, that’s the absolute ideal. I’m not a fan of historical or analytical texts that might interrupt the flow of a visual narrative. My ideal would be to create a book in which image and text are equally important.

You have just been honoured with the Prix HiP in the category ‘Publisher of the Year’. What does this award mean to you?

I am aware that the significance of receiving such an award is relative, and doesn’t mean that you have finally arrived. But I am extremely pleased to have been chosen, and have to admit that it has definitely put a spring in my step. Doing this work can be quite lonely and involve a lot of self-doubt regarding your editorial and graphics-related choices. Added to this are the continual demands of dealing with finances, distribution and media visibility. So to be recognised in this way has really affirmed my joy and dedication to the adventure that is lamaindonne.

Interview: Denise Klink

David Fourré+-

David Fourré has worked in publishing and graphic design for more than 20 years. His passion for photography inspired him to establish the lamaindonne publishing company in 2011, with headquarters in Marcillac-Vallon in the Southern-French Departement Aveyron. Lamaindonne currently offers a catalogue of some 15 books, the majority of which are monographs. Fourré has been honoured with the 2019 Prix HiP in the category ‘Publisher of the Year’. More

Gabrielle Duplantier, Terres Basses

Gabrielle Duplantier, Terres Basses

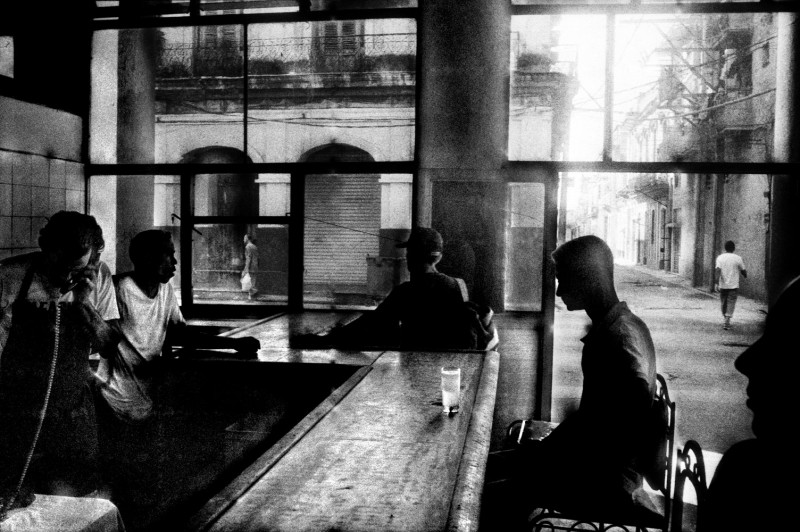

Gaël Bonnefon, Elegy for the Mundane

Gaël Bonnefon, Elegy for the Mundane

Gilles Roudière, Trova

Gilles Roudière, Trova