Less is more

Less is more

May 17, 2019

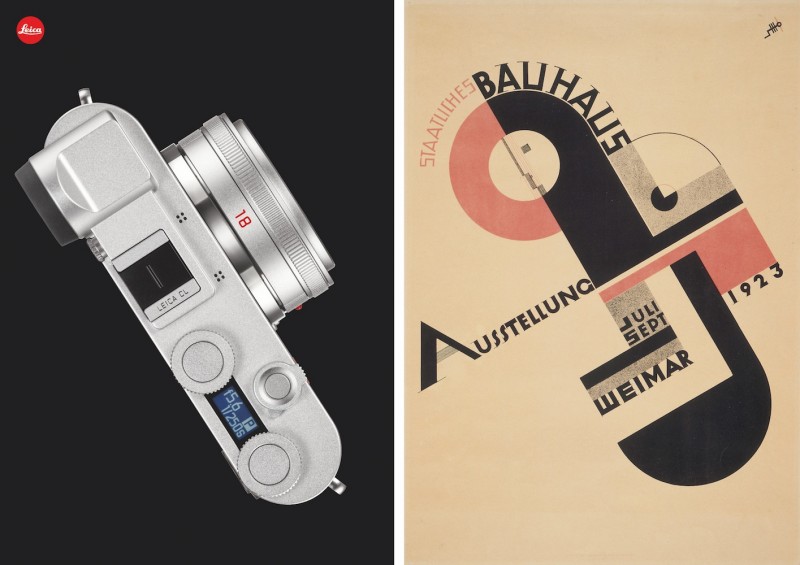

100 years of Bauhaus: Like no other educational institution, the ‘laboratory of modernism’ profoundly shaped the evolution of design, art and architecture in the twentieth century. Indeed, the movement’s decisive aesthetics have lost none of their impact to this day. It was established by amalgamating the Weimar Academy of Fine Arts with the city’s School of Arts and Crafts – thereby offering an unprecedented consolidation of fine-art and craft-based disciplines within one facility. Having laid the foundations for this

pioneering concept in Weimar, the Bauhaus school moved to Dessau in the former Free State of Anhalt in 1925, where it went on to experience its great heyday.

Bauhaus was connected with photography since the beginning: In 1923, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius invited the constructivist artist to lead the school’s metal workshop and foundation course, taking over from Johannes Itten. Moholy-Nagy’s theoretical writings largely revolved around his experiences with the Leica. In his book Painting, Photography, Film (published in 1925), he suggested that the purpose of photography should no longer be limited to a pure reproduction of reality. His reflections paved the way for photography to become a fully fledged form of creative expression.

The Bauhaus school only began to offer photography classes in 1929. The subject was taught by Walter Peterhans, whose drastically different approach placed a strong focus on craftsmanship, camera technique and precise dark-room work – though students were still given assignments involving experimental subject studies. Students used a variety of camera models, from the Rollei-flex (Irena Blühová) to the Linhof (Ellen Auerbach), and from a 9x12 plate camera (Eugen Batz) to a 6x9 (Gertrud Arndt). Some Bauhaus students did, however, own a Leica – for example, Erich Consemüller, Alfred Ehrhardt, Gotthardt Itting, Kurt Kranz, Hajo Rose and Moï Ver.

Other Bauhaus protagonists whose Leica-connections are worth mentioning include Josef Albers (a teacher at the Bauhaus from 1925 to 1933), as well as the avant-garde photographer Umbo (Otto Maximilian Umbehr) who, having studied at the Bauhaus from 1921 to 1923, went on to create much of his work with the Leica. Andreas Feininger and his brother, T(heodore) Lux Feininger, are equally notable; both of them first discovered photography at the Bauhaus school, where their father, Lyonel Feininger, was teaching as a so-called ‘master’. Inspired by his sons’ enthusiasm, Lyonel Feininger also turned to the Leica in 1931. Hungarian photographer Judit Kárász was among those who went on to create remarkable Leica images following their time at the Bauhaus, as was Edith Tudor-Hart (who later became an agent for the Soviet secret service).

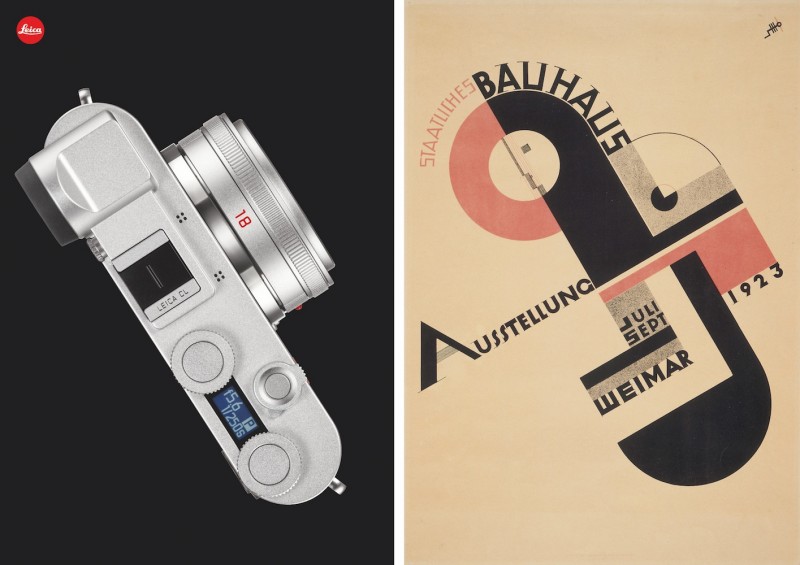

Yet despite the multi-faceted connections between Leica photography and individual Bauhaus protagonists, the essential legacy both the company and the school have in common is that they – each in their own way – have shaped the visual language of an era. To mark the centenary of the Bauhaus movement, Leica have released a special edition of the Leica CL. The “Bauhaus” set, which will be produced in a run of 150 units, comprises the silver-finish variant of the camera, accompanied by an Elmarit-TL 18 f/2.8 Asph (also in silver) and a leather strap. The anniversary set is also distinguished by the fact that the customary red Leica dot has been lacquered black. This feature alone makes the “Bauhaus” edition extremely unusual, not least considering that this type of discretion is usually reserved for Professional variants of the Leica M. With the ‘bauhaus’ imprint on the trim and strap also being very unobtrusive, the set perfectly reflects the movement’s unembellished aesthetics – and its core ethos of ‘form follows function’.

Bauhaus was connected with photography since the beginning: In 1923, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius invited the constructivist artist to lead the school’s metal workshop and foundation course, taking over from Johannes Itten. Moholy-Nagy’s theoretical writings largely revolved around his experiences with the Leica. In his book Painting, Photography, Film (published in 1925), he suggested that the purpose of photography should no longer be limited to a pure reproduction of reality. His reflections paved the way for photography to become a fully fledged form of creative expression.

The Bauhaus school only began to offer photography classes in 1929. The subject was taught by Walter Peterhans, whose drastically different approach placed a strong focus on craftsmanship, camera technique and precise dark-room work – though students were still given assignments involving experimental subject studies. Students used a variety of camera models, from the Rollei-flex (Irena Blühová) to the Linhof (Ellen Auerbach), and from a 9x12 plate camera (Eugen Batz) to a 6x9 (Gertrud Arndt). Some Bauhaus students did, however, own a Leica – for example, Erich Consemüller, Alfred Ehrhardt, Gotthardt Itting, Kurt Kranz, Hajo Rose and Moï Ver.

Other Bauhaus protagonists whose Leica-connections are worth mentioning include Josef Albers (a teacher at the Bauhaus from 1925 to 1933), as well as the avant-garde photographer Umbo (Otto Maximilian Umbehr) who, having studied at the Bauhaus from 1921 to 1923, went on to create much of his work with the Leica. Andreas Feininger and his brother, T(heodore) Lux Feininger, are equally notable; both of them first discovered photography at the Bauhaus school, where their father, Lyonel Feininger, was teaching as a so-called ‘master’. Inspired by his sons’ enthusiasm, Lyonel Feininger also turned to the Leica in 1931. Hungarian photographer Judit Kárász was among those who went on to create remarkable Leica images following their time at the Bauhaus, as was Edith Tudor-Hart (who later became an agent for the Soviet secret service).

Yet despite the multi-faceted connections between Leica photography and individual Bauhaus protagonists, the essential legacy both the company and the school have in common is that they – each in their own way – have shaped the visual language of an era. To mark the centenary of the Bauhaus movement, Leica have released a special edition of the Leica CL. The “Bauhaus” set, which will be produced in a run of 150 units, comprises the silver-finish variant of the camera, accompanied by an Elmarit-TL 18 f/2.8 Asph (also in silver) and a leather strap. The anniversary set is also distinguished by the fact that the customary red Leica dot has been lacquered black. This feature alone makes the “Bauhaus” edition extremely unusual, not least considering that this type of discretion is usually reserved for Professional variants of the Leica M. With the ‘bauhaus’ imprint on the trim and strap also being very unobtrusive, the set perfectly reflects the movement’s unembellished aesthetics – and its core ethos of ‘form follows function’.