Carloz Javier Ortiz – We All We Got

Carloz Javier Ortiz – We All We Got

Carlos Javier Ortiz

January 6, 2015

© Carlos Javier Ortiz

Carlos Javier Ortiz is a member of Facing Change: Documenting America, a collective of journalists aiming to compile a comprehensive insight into the social realities of contemporary America, with the intention of expanding public debate about the roots of social conflict. As a non-profit endeavour, Facing Change is dependent on donations. We All We Got was also completed as a crowd-funding project.

The project was almost nine years in the making. What was it that first prompted you to start it?

I slowly began to explore the topic in 2004. At the time, I lived in Philadelphia, and became aware that the city had almost exactly the same problems of youth violence as Chicago. So I started working in Philadelphia, before moving back home to Chicago in 2006. This was when I really began to think about turning it into a long-term project. After the deaths of two little girls in Chicago just eight days apart, I decided that I would commit myself to showing what challenges families and communities face after the trauma of losing their children to gun violence. Growing up in a lower-middle class home in Chicago, gun violence and gang life were not unfamiliar to me. In High School, one of my classmates killed a security guard in order to be initiated into his neighbourhood gang. There were fights every day after school over gang issues or perceived 'disrespect'. Some of my classmates brought guns to school for protection. Needless to say, it was a stressful environment. All of these experiences formed part of the motivation for We All We Got, my first long-term personal documentary project.

You have repeatedly witnessed children becoming the incidental victims of gun violence because they found themselves in the firing line of rival gang warfare. In the course of your work you grew close to their grieving families. How did you manage this, how did you explain your project to them and what effect did your presence as a photographer have on the situation?

I started this project as a photographic investigation into the lives of people who opened their hearts and trusted me to tell their stories. I not only photograph bereaved families during the immediate aftermath of violence, but I also stay connected with many of the people I meet in the course of my work. It is a matter of personal integrity to fully acknowledge their grief and loss at the time, but to also photograph moments of peace and even joy that occur over time. In this way, I hope to render the full humanity of all my photographic subjects.

The mother of the little girl nicknamed 'Nugget', who was shot dead only days before her eleventh birthday, put on a commemorative celebration every year up to what would have been Nugget's 18th birthday. You document this in your book. What is your perception of this case, and what emotions did it trigger in you?

Nugget's mother was one of the first people to really let me document her family. She wanted me to show people what her family was going through during and after their loss, and how their lives were impacted by this tragedy. Her story really motivated me to continue with this project. After photographing the celebration of Nugget's 18th birthday, I felt that it was time to compile these stories into a book.

The photographs in We All We Got are assembled in non-chronological order. What was your intention behind this presentation?

Essentially, the book is laid out in a non-sequential order because I believe that life is also non-sequential.

Your pictures highlight the disturbing fact that while empathy and solidarity within the neighbourhoods are clearly evident – for example in the rituals of shared grieving and commemoration, or in the protests against violent killings – the rituals of 'the street' (which are the very cause of the violence no-one seems to actually want) still remain at least as powerful. Why is it so impossible to break this vicious circle?

For many decades, society has neglected to truly address the underlying issues that exist in impoverished neighbourhoods. Although there is a pronounced altruism within the communities, outside help is desperately needed.

What is your personal take on the culture of violence you address in your photographs? How much of a role does the drug business play? As an illegal economy with an un-ending demand, promising fast money for those who can assert themselves, it must seem like the only available opportunity for those who feel abandoned by the American Dream, and the only way to gain the status symbols we bow to as a society. Is it fair to say that what we see here are the tragic results of racism combined with a failed, bigoted government approach to drug policy?

I believe that all of the above have an influence on the outcomes young people and families face today. Racism of course has always been at the forefront. Housing discrimination, segregation and the war on drugs have torn apart low-income neighbourhoods in Chicago and other US cities. Although the US has made significant progress since the civil rights era, poor families are essentially left to fend for themselves. In the most impoverished neighbourhoods, upper mobility is barely existent.

The death of Derrion Albert in 2009 was among the very few incidents you documented that was actually picked up by the national media. The rap artist NAS used it as an opportunity to write an open letter to the 'young warriors' of Chicago, in which he says that they are 'fighting the wrong war'. In your perception, did this have any effect on your protagonists and their immediate surroundings?

It is hard to pinpoint the effect of someone like NAS addressing young boys who are sometimes victims, sometimes perpetrators. But I do know that listening to Hip-Hop has influenced my own world view.

What is the feedback you have received so far in connection with your project?

The feedback has been insightful and an altogether humbling experience. I have learned about love and resilience. I have learned that humanity can be tragic and beautiful at the same time.

Do you feel that photographs can have the power to positively alter reality?

I believe that photographs can help change individuals. I don't believe that photographs can really change the whole world.

And lastly, what was your preferred combination of camera and lens for this project?

My Leica M9 with a 35mm and 28mm, and my Polaroid.

Carlos Javier Ortiz+-

Carlos Javier is a director, cinematographer and documentary photographer who focuses on urban life, gun violence, racism, poverty and marginalized communities. In 2016, Carlos received a Guggenheim Fellowship for film/video. Over the past two decades his career has evolved from photography to working in film and video. Although he consider labels to be limiting, he sees himself as a filmmaker and visual artist. Working in the medium of visual arts and journalism, for him, means freedom of expression and offers him a voice. Historical and contemporary political events have impacted his practice and influence his approach to his work. More

© Carlos Javier Ortiz

After the murder of a young man in a drive-by shooting people watch the police process his body, which is covered by a bloody white sheet. North side of Chicago, 2009

Siretha White’s family and friends lay flowers on her casket at her funeral. The shootings of Siretha and Starkeisha, only eight days apart, saddened and shocked the community. Both deaths were a result of gang violence with assault weapons. Chicago, 2006

Darius Brown was playing basketball with his friends at Metcalfe Park when a white car drove by and sprayed the crowd with bullets. The next day, the playground was stained with blood. Protests and a cry for peace followed. Bronzeville, Chicago, 2011

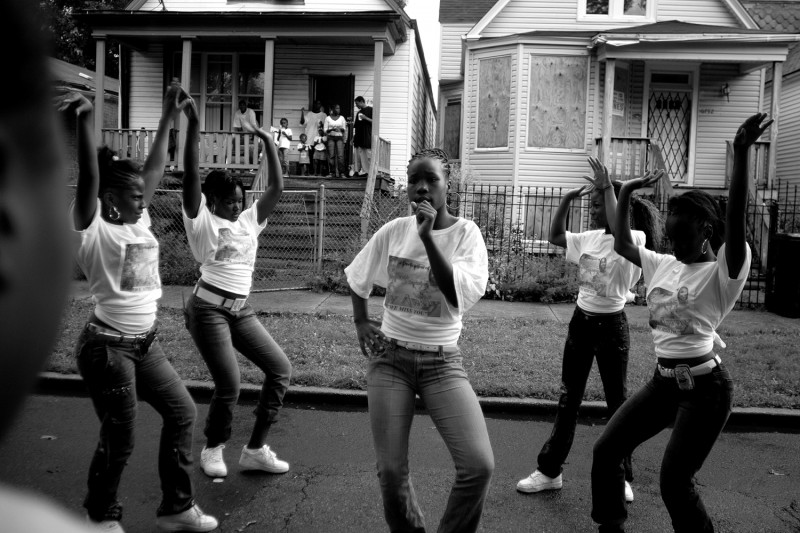

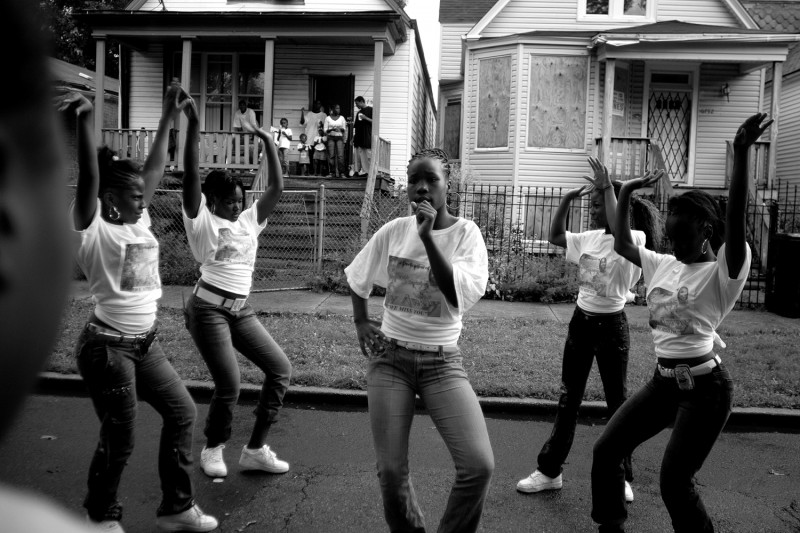

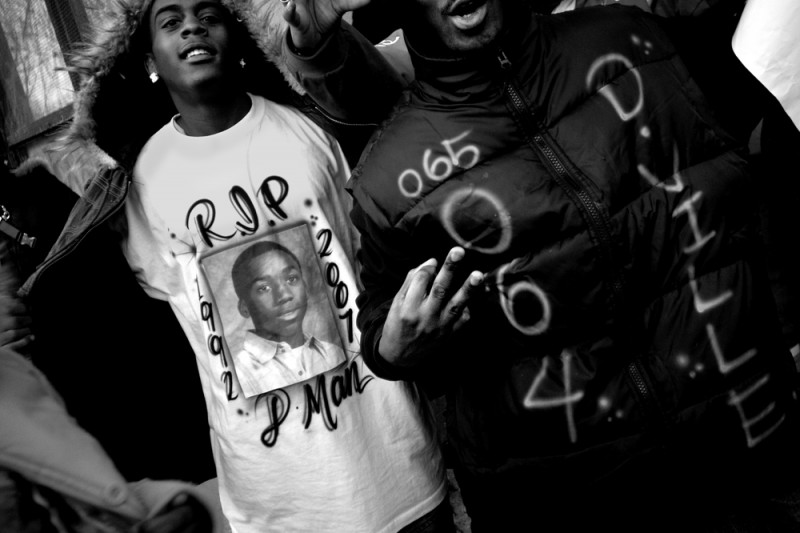

Darius Mitchell, 14, was shot and killed at a house party after a fight. The boy’s friends show off T-shirts made in his memory. Englewood, Chicago, 2007

Albert Vaughn was the neighborhood guardian, the older teenager who would play ball with the younger kids and try to keep them safe from trouble. About 50 of his friends and family members gathered to remember „Li‘l Al“ on the block where he was killed. Englewood, Chicago, 2008